Aubrey Abrakasa Jr. was killed 12 years ago, and his mother Paulette Brown has lobbied for justice for almost as long

On May 2, as one of his last acts as Police Commission president, Julius Turman presented Paulette Brown with a signed letter for the Department of Public Works that would protect her son’s crime bulletin posters from being ripped off telephone polls. For nearly a decade, Brown had been asking the commission, the mayor and SFPD every Wednesday for protection for her son’s homicide posters and answers to his cold case.

This August will mark 12 years that Brown’s son, Aubrey Abrakasa Jr., was killed in a shootout at Grove and Baker streets near his Western Addition home. The details are still threadbare 12 years later: it was Aug. 14, a quarter after 3 p.m., and Abrakasa had left his house. Some news stories say he was sending a warning, some say he was going to work and others claim it was a text message that compelled him outside. Over 30 rounds were fired. Over 10 struck him. He was 17 years old.

At her May 10 meeting with the Healing Circle for the Soul, Brown’s account is that Aubrey had noticed alleged gang members on his block, and yelled “run!” before being caught in a crossfire by warring gang members. She knows little more than she learned the day of his death.

“I been out there for the last 11 years in officials’ faces, not knowing what to do,” she said of finding out more information. Since her son’s case is technically “open,” she does not have access to his case file. Her son’s investigator, Jim Spillane, does not keep in regular contact with her and is not employed full-time by SFPD.

Sgt. Cunningham is a homicide detective currently five months into a cold case investigation of his own. Contrary to media portrayal, no two cases are alike, and there is no blueprint for handling cases without leads.

“There’s no set time or protocol. All homicides are open cases unless closed,” he said. “Some might be 20 years old but still volatile. Sometimes people feel more comfortable with time, sometimes not so much … I can’t create any new evidence.” Making cases and crime bulletins more visible and speaking on them at City Hall are, according to Cunningham, only potentially helpful.

“If somebody has a lead, I’m gonna be open to it. It brings recollections, but as far as beating down the door to get an answer, the evidence is there or it’s not there,” he said. The evidence he is referring to is witness testimony, for which Paulette and other parents blame “snitch culture,” because snitches get stitches, or worse.

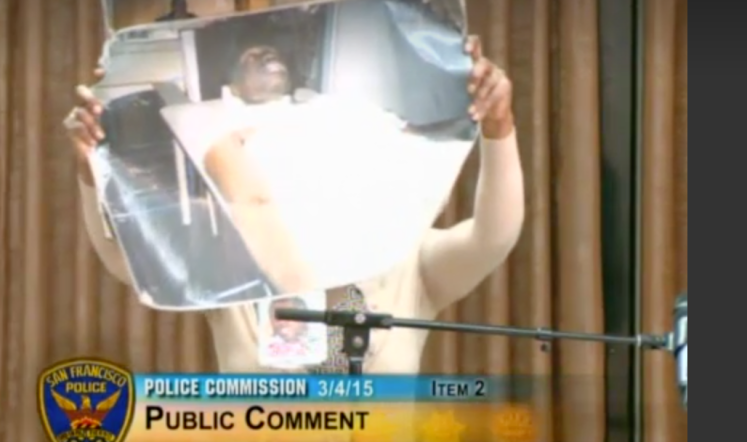

To catalyze the investigation, Brown attends the SF Police Commission meetings with unwavering consistency. She can be seen in every recorded meeting from this year thus far, holding up a picture of her late son with the highest possible reward for information: $250,000. Her appearances date back to at least 2010, and she is always seated in the front row, just right of the podium for public comment. Even when she is not speaking, her message can be seen: “Where were you when I was murdered?”

But Paulette Brown speaks. She knows what information can fit in two minutes, often the alloted public comment time limit, and she always requests use of the overhead. She shows the same documents: her son’s school picture, his crime bulletin reward, and the list of names of the men she says killed her son. In one meeting from September 9, 2015, she even holds up pictures of their faces.

Aubrey’s case has been in the news before, but over the years Brown feels they fail to capture the whole picture. He was her oldest son, his father was Nigerian, he was a good kid.

“It’s not about accommodation, it’s about accountability. I still want justice for my child. People think we get over it … we still have no closure. I don’t just fight for my son, violence is violence. My son has no voice. I’m his voice. I don’t want to be pacified,” she said of not being taken seriously.

The names she said came from the SFPD. She may not be far from the mark.

A 2009 article from SF Gate’s City Insider blog suggests that at the time, SFPD and former Mayor Gavin Newsom had identified six suspects. Brown claims they were all arrested that day, but let go due to lack of evidence.

“All six perps went to jail that day. The names are listed on the case file. There were people around but no one will talk,” she said.

According to testimony from Sergeant Damon Jackson in UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. ALFONZO WILLIAMS, Aubrey and his family live in the heart of the uptown gang Central Divisadero Players’ territory, which runs “from Divisadero Street to Central Avenue and from Fulton Street to Hayes Street.”

WEmap

A Paris Moffett, Hannibal Thompson and Maurice Carter are listed as Eddy Rock gang members in a 2007 case of PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, vs. CHOPPER CITY, EDDY ROCK and, KNOCK OUT POSSE, all gangs with turf in the Western Addition where Aubrey was killed.

Moffett, who San Francisco City Attorney Dennis Herrera confirmed as an Eddy Rock leader, was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2009 for gun and narcotics charges unrelated to Aubrey’s death. He was released on good behavior last summer, and is apparently pursuing a music career as rapper Playa P. His criminal history has not deterred him from performing alongside Bay Area artists San Quinn and Mac Mall, and the video for his new song, “Mainey,” was filmed at Eddy and Buchanan, which is Eddy Rock territory.

Hannibal Thompson is also the name of a Bay Area comedian who has acknowledged his criminal past in previous interviews but has not admitted to involvement with Abrakasa’s death. Neither responded to requests for comment.

The case is “cold” because despite Brown’s insistence, no witnesses have come forward and confirmed her accusations. Officer Ryan Jones doesn’t blame bad policing, just human nature.

“All cold cases become cold cases for the same reason: you hit a block. You need participation,” said Jones.

Abrakasa Jr. was on the basketball team at Wallenberg High School and worked at Bernal Heights Rec Center, but over a decade later few people can speak to his character. No employees at BHRC can recall working with him, and his record at Wallenberg High School is no longer available due to the time passed. Time does not heal all wounds, it makes them harder to find.

Paulette’s story is visible, but not unique. Every second and fourth Thursday of the month, she attends the Healing Circle for the Soul, a support group started in 2004 for parents and family members who had lost children, most to murder. Paulette is the glue: she brings snacks, including cherries, bananas, danishes, cheese and crackers; she pours everyone a cocoa or apple cider.

The group say prayers, release anger and grief and brainstorm ways to make their cases and needs more visible. Some cases, like member Floyd’s son’s murder, have been solved. Most remain unsolved and stagnant.

Mary Bow’s son Allen Bow was shot and killed in 2007 walking down Polk Street.

“I don’t eat, I don’t sleep. I suffer from PTSD, bad. I’m a completely different person, in everything I do,” she said.

For Paulette and the group, the next step is organizing a meeting with Mayor Farrell, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, and eventually, hopefully, the FBI.

“The squeaky wheel gets oiled. I believe that.”